The Big Dumb Object List

Big Dumb Objects collected from the blog.

Missile Gap (Alderson disk)

Missile Gap (Alderson disk)

I’ve been meaning to blog Missile Gap, a novella by Charlie Stross available online at Subterranean Press, since I read it a couple of weeks ago at the start of my current Big Dumb Object/megastructure phase. I spotted “Missile Gap” making the rounds at del.icio.us and was reminded to link it for its Alderson disk, if nothing else. Here’s part of the novella’s blurb:

It’s 1976 again. Abba are on the charts, the Cold War is in full swing — and the Earth is flat. It’s been flat ever since the eve of the Cuban war of 1962; and the constellations overhead are all wrong. Beyond the Boreal ocean, strange new continents loom above tropical seas, offering a new start to colonists like newly-weds Maddy and Bob, and the hope of further glory to explorers like ex-cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin: but nobody knows why they exist, and outside the circle of exploration the universe is inexplicably warped.

Infinite Flat Earth

BDO of the Day: Infinite Flat Earth

Via deli.cio.us: in his blog entry of new, post-Singularity ideas, Rudy Rucker describes a variant of the Alderson disk. Here’s his even bigger Big Dumb Object:

What if Earth were an endless flat plane, and you could walk (or fly your electric glider) forever in a straight line and never come back to where you started? The cockroach zone! The kingdom of the two-headed men! One night there’ll be a rumble and, wow, our little planet will have unrolled, ready for you to start out on the ultimate On the Road adventure.

I know it’s a sign science fiction is dying that I’m tempted to say that this infinite flat earth, like many of his other fresh ideas, is not science fiction at all. It’s more of a planetary romance on an infinite backdrop; it’s science fantasy.

Update (9/11/2017)

To actually make an artificial infinite flat earth megastructure, you would need an empty universe (which, presumably, we’ll have some day) and some artificial suns whizzing by overhead, perhaps at the expected rate for a 24-hour day. And some construction process keeping ahead of the marching sword-and-sorcerers.

Epic Genre Objects

Epic Genre Objects

As part of a post critiquing this season of Game of Thrones, Vox Day made an epic fantasy list which led to some discussion at File770. The implied definition of “epic fantasy”, considering that GRRM’s work prompted the list, is fantasy of worldwide scope (for the fantasy world) with multiple, unrelated viewpoint characters.

While it took another whole post for Mr. Day to explain Stephen Donaldson’s place on his list, the first post explains why the list is so short, surprising, and unfamiliar after #2 or so: the tragedy of epic fantasy is that it’s usually bad. In fact, it’s surprisingly bad. If something came to mind as a (complete) epic fantasy favorite of yours, chances are it’s either Tolkien or not epic fantasy at all. It’s so bad because it’s so hard to write, and even those who start out well (George R. R. Martin, in this case) tend to falter somewhere along the way.

Personally, I don’t read much fantasy because I find all of it is hard to get right, not just the epics—at least judging from the outcome. I have no notable corrections to make to the list; like Day, I would have to write it myself to get an epic I liked even half as much as I like Tolkien. So I steeled myself to start reading books from the list. But, in a saving throw that reminded me of the death of Vogon poet Grunthos the Flatulent, my brain rebelled and instead started in on another big dumb object (BDO) phase.

My favorite new BDO is a Topopolis, a toroidal (or knottier) O'Neill habitat of big, dumb dimensions. Sadly, there are no few books about them, so I’ve been reading about Dyson spheres instead. Peter suggested I maintain a BDO list, but Wikipedia seems to have that well in hand. Instead, I’ll just recap the ones I’ve read in this go around:

Orbitsville (1975) and Orbitsville Departure (1983) by Bob Shaw are the first two books in a series of three about a cling-to-the-inside Dyson shell (requiring alien magic-levels of engineering). I haven’t dug up the third book yet, and the second frittered away a lot of time on Earth instead of inside Orbitsville, but overall they were an entertaining read.

Search for the Sun (1982) by Colin Kapp is the first in his series of four Cageworld novels about matrioshka (nested) Dyson shells. While these are usually proposed for computation, this set is used for habitation, and are getting full. The exploration and discovery of this massive structure is a little unbelievable in the sheer luck required, but that’s adequately papered over (I hesitate to say “explained”) by the end of book one. Presumably the other three are about solving the immense malthusian trap that these fully-populated concentric shells represent. The writing is entertaining, and I give it points for actually over-populating a BDO. I don’t see a reason yet not to read the other three.

Hex (2011) by Allen Steele is a one-off set in his Coyote universe. It’s good to see an interesting new BDO, but I felt the math was a bit off on this one. The author describes an individual biopod at one point like this: “A thousand miles long and a hundred miles wide[…] You can fit a small continent in here.” Sadly, that’s not true. Australia is a small continent, at just under 3 million square miles. A hundred thousand square miles is more along the lines of New Zealand or the state of Colorado (just over), or Great Britain (just under). Now yes, there are a lot of these in the full BDO (a rotating-for-gravity chicken-wire sphere with the biopods laid out in pairs on the sides of the hexes), but they’re isolated from each other and small, making the thing feel, ecologically, more like an infinity of zoo pens than thirty-six trillion new world to settle.

The plot of Hex relies on humans behaving stupidly and aliens withholding information, and has been harshly critiqued elsewhere—perhaps too much, since human stupidity seems to be the author’s point in more works than just this one. The original Coyote novels seem to have fared better with the critics; I recommend starting there unless you’re a hard-core BDO fan like myself.

Next up: Across a Billion Years.

Hex

BDO of the Day: Hex

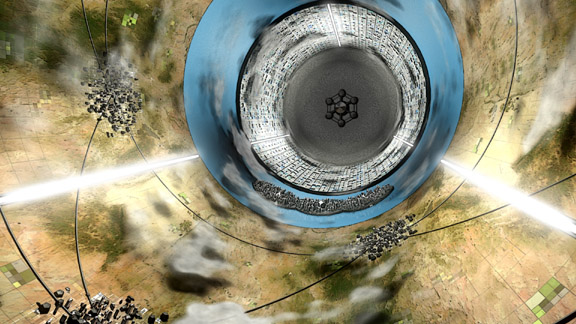

The Big Dumb Object (BDO) of the Day comes from yesterday’s long post: the Hex is a BDO invented by Allen Steele in the eponymous Coyote universe novel. It’s quite similar to a Bucky Habitat, a skeletal Dyson sphere formed of O'Neill colonies, but instead of the segments spinning individually, the entire sphere rotates to generate gravity like a Ringworld.

The Hex is a hexagon-tessellated, hollow, non-solid sphere of radius 1AU, with a sun at its center. (No mention is made of the twelve pentagons required to hexagon-tessellate a sphere.) The sphere also surrounds the decayed orbit of the homeworld of the species that constructed the Hex.

Cylindrical biopods are laid out in pairs on the sides of the hexes. The hexagons formed by the biopods are mostly empty space, but are strung across with cables supporting small, movable solar sails to collect energy and correct for any orbital perturbations of the sphere. Biopods are linked by separate structures, nodes, at the vertices of the hexagons, which house docking bays for spaceships. The biopods are numbered for navigation, and automatic tramways run along the biopods and through the nodes, connecting all of the biopods.

Each biopod is 1000 miles long by 100 miles in diameter—about the size of Colorado, but more like two Tennessees laid out the long and skinny way. The novel claims a total of 6 trillion hexes with 36 trillion biopods for a total of 3.6 quintillion square miles (the equivalent of 18 billion Earths at 200 million square miles per Earth). But according to my calculations there would only be about a quarter-trillion hexes, so one and a half trillion biopods and only 150 quadrillion square miles (750 million Earths). Needless to say, either number qualifies the Hex as a BDO, although the size of an individual biopod may not be adequate to maintain a biosphere without outside help. (One out of every six biopods is not an actual biopod but some sort of recycling center used to maintain the others, and to which the builders do not permit access; the square mileage numbers have not been adjusted for that.)

The sphere’s rotation gives a gravity range of 0g to 2g, depending on latitude. Individual biopods have a self-healing transparent sky surface facing the sun which darkens to black to simulate the diurnal cycle of whatever planetary environment is being reproduced. Various landforms fill the lower half of the cylinder; they generally seem to feature a river valley, fed from one end of the biopod, rising to more mountainous terrain along the walls and requiring an escalator to reach the valley floor from the point where the trams let out.

At least one hexagon full of biopods and cabling has been removed from the Hex, and others are reportedly unfinished. The BDO is not abandoned (as they so frequently are) but is still inhabited and regulated by its creators, apparently as an interstellar nature preserve in which weapons and warfare are forbidden. Several extinct and unknown (except to the creators) species can be found here, if you’re willing to look (peacefully) through the trillions of biopods for them.

Commentary

It’s not clear to me that the structure of the hex in any way solves the stress issues of rotating a megastructure to produce gravity. According to my new favorite tool, SpinCalc, the sphere’s tangential acceleration would be about 4 million miles an hour, whipping around the sun in less than a week. The author doesn’t mention the stresses involved or the magical materials usually required to build such a BDO; his aliens seem more concerned that their recycling secrets will be discovered, not that their BDO will be mined for its unobtanium. So I think he would have been better off with a traditional Bucky Habitat and rotating O'Neill cylinders.

Personally, if I were making such a BDO I would cut down the number of biopods and make each one bigger in the McKendree cylinder style, say 10,000 miles long by 1,000 miles diameter (10 million square miles, the equivalent of a good-sized continent like North America). This would yield about 420 million hexagons, and because I’m not doubling them up, only one and a quarter trillion habitats. Their area would be 12 quadrillion square miles (63 million Earths).

If that seemed insufficient, I could make the BDO in the other Bucky Habitat style, geodesic, which would add a star of six more habitats in the center of each of my hexagons (and five in the few pentagons), for an approximate total of 3.75 trillion habitats, 38 quadrillion square miles, and 189 million Earths. Approximately.

Rama

BDO of the Day: Rama

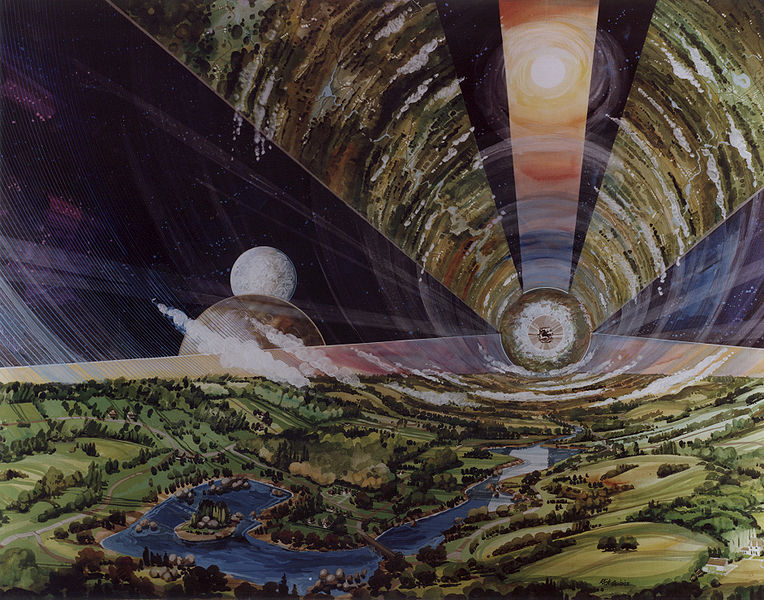

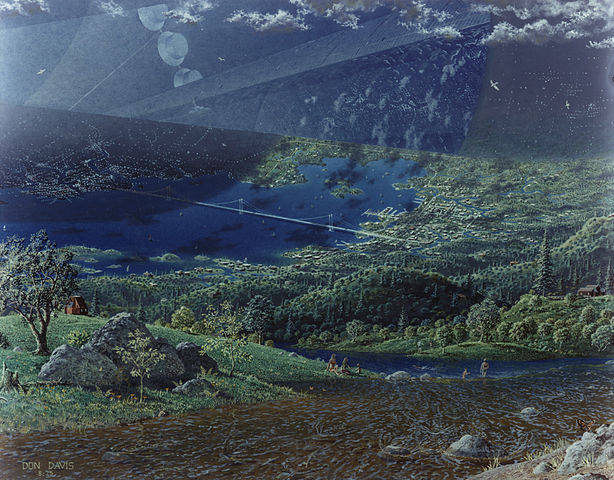

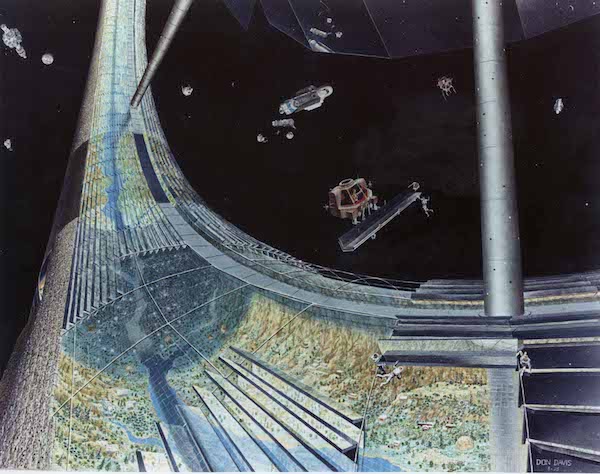

Today’s former Big Dumb Object (BDO), the McKendree cylinder, has been postponed until tomorrow in favor of Rama. Rama also requires an explanation of a smaller object, the O'Neill colony or cylinder, so I’ll start there:

In 1974, Gerald O'Neill published a design for a space habitat that could be built with materials from the Moon or asteroids and would contain an Earth-like biosphere. The cylinders would be 16 miles long and 4 miles in diameter (200 square miles of surface area each), large enough to spin for gravity without ill effects for most people. Two cylinders would be paired for attitude control, pointing at the sun. The surface area would be divided equally between stripes of land and of window running lengthwise (3 of each in his original design), meaning that there would only be 100 square miles of land inside. The windows would admit indirect sunlight via mirrors and also allow heat to radiate by looking directly on space. His design incorporates steel structure and cables, though he thought better metals might be available.

Rendezvous With Rama (1973) by Arthur C. Clarke features a single cylinder about double the size of an O'Neill cylinder (and disproportionately fatter), which spins for gravity. Rama, however, is an interstellar craft with a drive system and no windows, though the layout of its artificial lighting strips is similar to O'Neill’s plan. Despite the similarities, Clarke is believed to have come up with the idea independently.

Although small in scale by BDO standards at only 31 miles long and 10 across (not quite a thousand square miles of land—smaller than Rhode Island), Rama is a classic BDO in that the humans exploring it are struck dumb by its proportions and lack of apparent purpose. Rama seems uninhabited despite its city-like structures; the promising discoveries the explorers make don’t help them much. All is eventually made clear in the three sequels, but they weren’t written by Clarke himself and their focus on contemporary issues may date them compared to the first book. YMMV.

Sadly, that Rendezvous With Rama movie I was hoping for never happened.

Update (4/25/2018)

Isaac Arthur devoted an entire video this week to O'Neill cylinders.

McKendree Cylinder

BDO of the Day: McKendree Cylinder

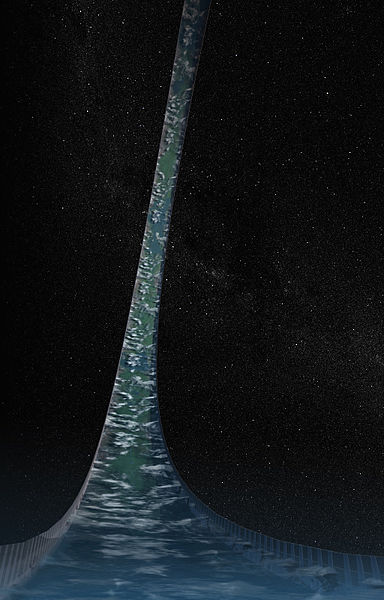

Today’s Big Dumb Object (BDO) isn’t as big and dumb as some, but it forms an essential building block of several truly big yet scientifically feasible BDOs. The McKendree cylinder is the big brother of the O'Neill colony or cylinder discussed in the Rama post. In short, an O'Neill colony is a pair of cylinders 16 miles long and 4 miles wide each rotating for gravity, with half the inner surface devoted to windows running lengthwise, leaving 100 square miles of usable land per cylinder.

In 2000, Tom McKendree super-sized this classic design to 5 million square miles using a new material: carbon nanotubes. His design measured 2900 miles long by 580 miles in diameter, but only 2.5 million square miles of land due to the windows (somewhat smaller than Australia). Theoretically these dimensions could be increased to as much as 6000 miles long by 1200 miles in diameter, for an area of 24 million square miles, at least half of which would be land (so a bit larger than Africa).

These cylinders are still intended to be paired (unless incorporated into even larger structures), so the Orion’s Arm Project suggests nesting them rather than attaching them side by side, and remarks that with even more floors a McKendree cylinder can easily rival the Earth in surface area.

Rungworld

BDO of the Day: Rungworld

Today’s Big Dumb Object (BDO) is the Rungworld, a ring-shaped ladder whose rungs I’ve covered before: O'Neill colonies (paired rotating cylindrical habitats at least 20 miles long and 5 miles in diameter) or their larger cousins, McKendree cylinders, neither of which can be made much larger using known materials. Instead, we make them bigger and dumber by attaching more than two of them together in a ladder shape. The rungs rotate individually for gravity as usual, and the sides of the ladder serve to hold the individual cylinders in place. We can make a smallish ring (along the lines of a Banks Orbital) this way, or a huge sun-spanning circle like a Ringworld (except feasible).

The Rungworld has not appeared in fiction outside of Orion’s Arm (nor are they guaranteed to appear in the books linked below; I haven’t read them yet). Isaac Arthur also discusses Rungworlds in several of his videos. He suggests using the sides of the ladder for transportation between the individual rungs.

Against a Diamond Sky: Tales from Orion’s Arm Vol. 1

After Tranquility

Bucky Habitat

BDO of the Day: Bucky Habitat

Today’s Big Dumb Object (BDO) is a Bucky habitat, a skeletal arrangement of rotating-for-gravity O'Neill or McKendree cylinders into a larger structure. Bucky Habitats are classified as having either a triangular or hexagonal arrangement, and any other arrangement is called a Kepler habitat instead. (The rungworld is not a Kepler habitat because the sides of the ladder are not themselves habitats.)

It’s not clear who first invented the Bucky Habitat, nor is it clear whether any particular arrangement (say, a closed structure) is intended or required. Orion’s Arm mentions a Bucky Habitat in the shape of a Dyson sphere along the lines of the Hex, but larger, and also shows a much more complex Kepler habitat called Kepleria.

Bucky Habitats have not appeared in fiction outside of Orion’s Arm and the variant seen in Hex, but Isaac Arthur discusses them in, for example, this video, where he mentions another name for them: polyhedral habitats.

Topopolis

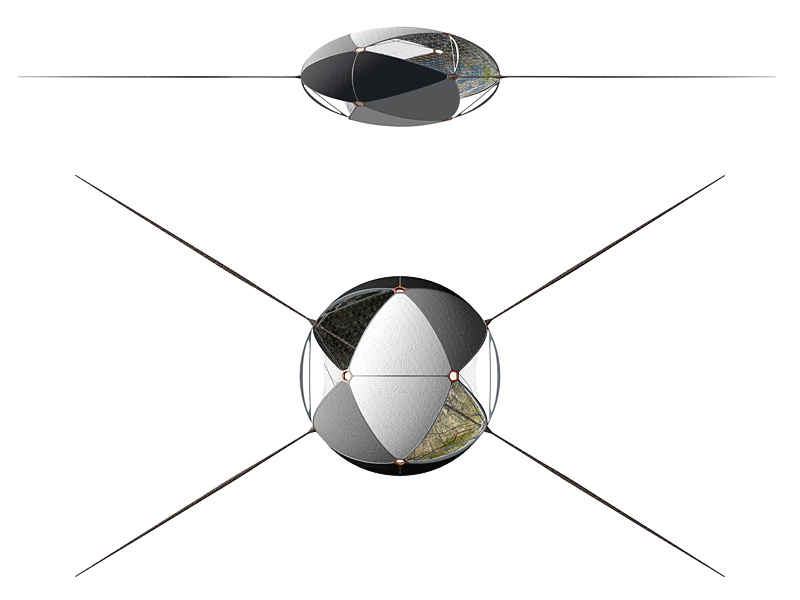

BDO of the Day: Topopolis

I mentioned today’s Big Dumb Object (BDO) in a recent post because I find it one of the most practical of the lot: a Topopolis is a toroidal or knottier O'Neill cylinder or McKendree cylinder stretched out lengthwise to big, dumb dimensions. Yet any spacefaring civilization could make one with materials at hand.

A topopolis rotates O'Neill-wise around its cylindrical axis, which is far more physically plausible than rotating around the sun at its donut center. At 1 AU long, compression of the topopolis as it rotates inward is negligible, well within the strength of non-magical materials like steel or carbon nanotubes. For similar reasons, only the short curve (around to the skylands) would be visible to someone standing on the inside of a topopolis; in the long direction the tube would appear to be perfectly straight.

In his classic megastructures essay, Larry Niven credited the Topopolis to Pat Gunkel under than name, but he also nicknamed them Cosmic Spaghetti. He didn’t seem to think they needed to be closed (others do); instead he envisioned them growing unchecked into other star systems:

With the interstellar links using power supplied by the inner coils, the tube city would expand through the galaxy. Eventually our aegagropilous galactotopopolis would look like all the stars in the heavens had been embedded in hair.

A topopolis’s orbit around a sun is unstable in the same way a ringworld’s is (as dramatized in Larry Niven’s The Ringworld Engineers), so some active provision must be made to keep it in place over the long haul. One notable feature you can build into a topopolis, mentioned at Orbital Vector and elsewhere, is a single river flowing all the way around the topopolis the long way—which is to say, for at least 1 AU or 93 million miles.

Orbital Vector has more details about topopolis construction, although they seem to assume that light coming directly in the windows can provide a day/night cycle. That isn’t practical at the spin rate of either type of cylinder; the original O'Neill or McKendree cylinder designs solve this problem by pointing an endcap at the sun and lighting the cylinder indirectly, but a topopolis has no such end. Even with carbon nanotubes, the maximum diameter of a McKendree-style topopolis is just under 1000 miles, so the slowest it could be turning to provide gravity is 48 times a day. An indirect lighting plan is required, such as artificial light, slow glass (i.e., magic), or a layer of shade material rotating more slowly than the inner tube.

Not subtracting for windows, at maximum diameter the McKendree style of topopolis provides about 300 billion square miles of surface area, or 1500 Earths, for a single loop around the sun. (A single topopolis can circle the sun more than once in a torus knot, and each loop in that case would be longer than 1AU.) The most modest O'Neill style is 10 miles in diameter (and can be constructed without carbon nanotubes), yielding only 3 billion square miles of surface area, or 15 Earths for one loop around the sun.

Although they’re big, dumb, and practical to build, topopoles are relatively rare in fiction, appearing in Matter (2009) by Iain M. Banks, White Light (1998) by William Barton and Michael Capobianco, in the background of Learning the World (2005) by Ken MacLeod, and, of course, at Orion’s Arm. You can’t go wrong with Iain Banks, but be warned: most readers complain about the sex in White Light. As an Amazon review put it, “it’s as if the cast of a bad porno movie was suddenly transported into what would have otherwise been a fascinating SF novel.”

Bernal Sphere

BDO of the Day: Bernal Sphere

A Bernal Sphere is the space habitat cousin of the most famous BDO of all: the Dyson sphere. First proposed by Bernal in 1929 with a 10 mile diameter, it reappeared in smaller form in the 70s as two of O'Neill’s space colony proposals: Island One (1600 foot diameter), and Island Two (a mile in diameter). The total inner surface of such spheres is about 300 square miles (Bernal), a quarter of a square mile (Island One), and 3 square miles (Island Two), respectively.

A Bernal sphere rotates to provide gravity, and as a result only an equatorial band has adequate gravity to be inhabited, with the remainder of the sphere devoted to windows, trees, and other purposes. This reduces the usable area, making it a relatively impractical layout compared to cylinders and other shapes (even though it photographs well).

Note that a real Dyson sphere is far too large for the curvature of the sphere to be visible.

BDO of Talk Like a Pirate Day: Virga

BDO of Talk Like a Pirate Day: Virga

Today is International Talk Like A Pirate Day, so I’ve picked a pirate-themed BDO for the Big Dumb Object of the day: Virrrrrga—I mean, Virga—is a carbon-nanotube sphere 5000 miles in diameter, enclosing 65 billion cubic miles of volume. It’s is a weightless environment filled with a breathable atmosphere circling a real sun at some distance, in which smaller habitats are rotated for gravity and artificial suns provide light and heat. It’s the steampunk setting for Karl Schroeder’s eponymous airship series beginning with Sun of Suns and including Pirate Sun.

The science behind Virga is explained on his website. Schroeder explains why he gave Virga a relatively modest size, though a balloon environment like his with an Earth-like atmosphere could be almost 22,000 miles across (5.5 trillion cubic miles of space), while a lighter atmosphere permits a sphere about 250,000 miles across (8 quadrillion cubic miles). Plenty of rrroom for pirates!

Dyson Shell

BDO of the Day: Dyson Shell

Today’s Big Dumb Object (BDO) is a Dyson shell, otherwise known as a Type II Dyson sphere. (A Type I Dyson sphere is big and dumb, but not an object: it’s a swarm of smaller objects in separate orbits, enough to use and block all the light of a sun.) A Dyson shell is impossible to make with any technology we know of; the gravitational stresses on it are too great for any known materials to withstand. In addition, a Dyson shell has no gravity to hold land, atmosphere, or inhabitants to its inside (see the shell theorem for proof), and negligible gravity on its outside. (These issues are usually solved using technology that’s indistinguishable from magic.)

image by Adam Burn

image by Adam Burn

The usual size of a fictional Dyson shell is 1AU in radius, giving it a surface area of a hundred quadrillion square miles—the equivalent of 550 million Earths. That’s big. Very, very big. So big that if you were inside it, it would not look curvy (as it is so often illustrated) but absolutely flat. You would not see the continents above you (as it is so often described) because the ones overhead would be astronomically far away, and there would be immense quantities of atmosphere between you and any “nearby” land. Peeking in through a hole or airlock (as is so often done) would require the same instrumentation as looking a quarter of the way around a solar system does.

One begins to see why Dyson regretted naming the lot of them, wishing instead that Olaf Stapledon would get the credit he deserved. (They first appeared in 1937 in Stapledon’s novel Star Maker.) Nevertheless, the impossible shells are quite popular with fiction writers, and even made it into a particularly execrable episode of Star Trek: The Next Generation. Dyson spheres loom over the Orbitsville series, the Cageworld series, and the two Farthest Star books, and are seen in passing in many other works, such as Across a Billion Years.

Note: The BDO series will be appearing less frequently from now on, although I still expect to post several times a week and not to run out of notable BDOs before NaNoWriMo at the earliest.

The Chindi

BDO of the Day: The Chindi

Today’s Big Dumb Object (BDO) is the chindi, a mysterious alien ship in Jack McDevitt’s eponymous book. It’s a little small by my own standards, but has occasionally been mentioned as a BDO (e.g., in this review by Russ Allbery).

Chindi was first published in 2002, but I reread it recently and it definitely holds up as a science fiction novel, though perhaps not so much so as a BDO novel. The novel falls around the middle of McDevitt’s Priscilla “Hutch” Hutchins, or Academy, series. (Spoilers follow for Chindi, but not for the rest of the series.)

About half the novel is devoted to investigating smaller stuff than the BDO: a mysterious signal that turns out to be a mysterious spy satellite, that itself turns out to be part of a mysterious network of such satellites, leading a group of human explorers from star system to star system. The systems are inhabited, formerly inhabited, or otherwise interesting, and space is dangerous, leading to plenty of drama before the BDO is revealed.

In one of these star systems they find the ship responsible for producing and sending out the satellites, whose purpose turns out to be spying on primitive alien cultures (alien to the makers of the chindi, so including humanity back when we were primitive). The ship gives itself away by having made its own red spot (well, a white spot) on a gas giant in order to suck fuel out of its atmosphere. It’s an asteroid-looking thing that is 16.6 kilometers long by 5.1 kilometers wide by 0.8 kilometers high, but it has exhaust tubes.

They choose a Navaho word for spirit to refer to it and decide to board it (one of a series of risky decisions the explorers have been making throughout the novel, leading to an ever-diminishing number of explorers, not to mention ships, involved in this expedition). But the exploration is predictably interrupted by the start of the high-speed trip the chindi has been gathering fuel to make, and much of the rest of the novel is devoted to the physics and gymnastics of rescuing (or losing) people in this predicament, rather than to the interior of the chindi per se.

The humans discover a warren of corridors inside the ship; off of each corridor are countless rooms ready to be filled, or already filled, with archaeological exhibits assembled (how, we never discover) by the chindi in its travels. Careful examination is made of a few of these chambers. The ship has artificial gravity; during an adventure involving an antigravity shaft, Hutch estimates that the ship is about 80 decks high in both directions; despite extensive exploration, no estimate is ever given of the number of chambers found on these 160 decks.

A few robots haunt the halls, ignoring the interlopers, but the engine room isn’t mentioned and no living aliens are found inside. The source and ultimate purpose of the chindi is not discovered in the novel, so it retains an air of mystery appropriate to a BDO.

Orbitsville

BDO of the Day: Orbitsville

Today’s Big Dumb Object (BDO) is Orbitsville, the Dyson sphere appearing in the eponymous novel by Bob Shaw and its sequels. I gave a brief review of the first two in a recent post.

Orbitsville is a traditional Type II Dyson sphere of the sort that made Dyson regret his association with them: made of a thin shell (“only a few centimeters thick”, later upped to 8cm) of magic material (“ylem”), magically radiating no heat or other energy from its central sun, with an environment magically clinging to the inside of the shell in violation of the shell theorem.

Orbitsville is the name used by its discoverers, but it is officially called Lindstromland, then later Optima Thule, by the wider human society. Human explorers first detected Orbitsville because it does have the expected amount of gravity for a Dyson shell enclosing a sun. Its reported diameter is “some 320,000,000 kilometers”, giving it a radius of “just over” 1 AU. Its outer surface is described as perfectly smooth (yet with “a reasonable index of friction”), perfectly spherical, and impervious to all forces possessed by humanity, which got there with a faster-than-light drive based on some invented post-Einsteinian physics.

The sphere rotates at 70,000 kilometers an hour at the equator, which is not the tangential acceleration required to produce gravity (4 million kph); at some point the humans note that the gravity is, instead, “synthetic”. The sphere blocks all radio signals with a (magical) dampening field, as well as the humans' interstellar drive (apparently not by magic but only for lack of the interstellar dust it uses for fuel). The explorers prove able to travel inside the sphere by more primitive means such as airplanes and the like.

The inside surface is “625,000,000 times the total surface of Earth”, which the characters estimate is about “equivalent to five billion Earths” worth of usable land (since most of the area of the Earth isn’t useful, whereas most of Orbitsville is). A rotating shade structure around the sun—a “globular filigree of force fields”, which even the author put in scare quotes—produces both seasons and alternating bands of day and night.

The sphere has a single circular opening at the equator, plus more blocked openings discovered and reopened later in the story. The first opening is about a kilometer in diameter and is protected by a (magic) force field through which a person (or a ship) can pass.

The sphere appears to be a classic abandoned BDO, with several species unrelated to the builders having come across it over time and settled within. More details about the builders and the apparent abandonment are revealed in the sequel, but BDO-wise we only get the added detail that there are 207 openings at the equator spaced about five million miles apart, plus a ring of 173 in the northern hemisphere and 168 in the southern hemisphere; all “vary a little in sizing and spacing”.

The first sequel is, frustratingly, mainly set mainly on Earth, but there is some BDO action at the end, and Orbitsville does loom over the human race thematically for the entire series. Earth was overpopulated with a constant stream of emigrants heading to its one colony world when humanity found Orbitsville, which becomes their new destination. Even in the first book, the characters voiced dark suspicions about the ultimate purpose of the BDO and the risk of humanity’s devolving to a primitive agricultural level within it as many races had apparently done before. But such misgivings don’t slow the exodus one bit; by the second book the Earth is nearly abandoned, and the true purpose of the BDO is revealed.

I didn’t find the notion that vast croplands would turn humanity back into subsistence farmers particularly convincing, but that’s not for any want of effort on the author’s part. His theory is at least superior to that of other authors who project our current interests and lifestyles onto a BDO setting infinitely, perpetually, and thoughtlessly.

The third book is harder to find and I haven’t read it yet, but reviews indicate that there isn’t much more there about the BDO qua BDO.

Double Dyson

BDO of the Day: Double Dyson

Today’s Big Dumb Object (BDO) is a double Dyson, a pair of nested Dyson spheres intended to solve the gravitational issues of a single Dyson sphere by creating a volume of atmosphere under microgravity between the two spheres. The inner shell would be transparent to the inner sunlight. In his classic megastructures essay, Larry Niven credits Dan Alderson (of disk fame) with the idea.

Living in a double Dyson would be like living in Virga, but without the pesky microsuns, complicated currents, or ice issues. Also, it would have orders of magnitude more space: inside a double Dyson you could pack about 5 billion Virgas into a layer one Virga deep.

Not much has been done with Alderson’s spheres in fiction or non-fiction, because it’s even harder to make two Dyson shells than one, one was already impossible by any known science, now one needs to be transparent to boot, and there’s still no gravity to speak of in there. So there is no standard depth to the living space enclosed between the shells. The actual living (floating) space of a double Dyson one AU in outer diameter and one Virga deep (5,000 miles) would be about half a sextillion cubic miles. At a more generous million miles deep, the volume would be a hundred sextillion cubic miles.

Roomy, if you enjoy floating around like that.

Megasphere

BDO of the Day: Megasphere

At galactic size, today’s Big Dumb Object (BDO) may be the biggest and dumbest out there. The Megasphere is a Dyson sphere with a surface area of “tens of millions of light years” [sic] built around a galactic core. As with a double Dyson, people would enjoy a Virga-like life in the space above the sphere. They would have to adapt to the microgravity, but would have an atmosphere that was “scores of light years” deep, in which they could build other megastructures and float between them at their leisure.

The megasphere is apparently the creation of Larry Niven, who described it in his classic megastructures essay without crediting anyone else. He also doesn’t mention the heat and drag effects of rotating huge megastructures within a vast atmosphere, never mind the more basic issues of radiating heat from the depths and of the atmosphere collapsing upon itself without magic to counteract the force of gravity.

Dural's World

BDO of the Day: Dural's World

Today’s Big Dumb Object (BDO) is a small but fresh example of the bioship whose passengers have forgotten they’re not on a real world. In episode 4, “If the Stars Should Appear”, the crew of the Orville are out star charting when they stumble across a vast ship drifting in space. Inside they find a flat biosphere under a curved dome that they describe as the size of New York City. The inhabitants worship a god named Dural (except for the rebels whose suspicions about the ship are heresy). Heretics are tortured and killed, medieval-style.

The engines are merely broken, rather than perverse in the manner of For the World Is Hollow and I Have Touched the Sky, so our heroes spend most of their time fighting the powers that be, gangland-style. (McCoy figured out the secret of Yonada by marriage.) Dural turns out to have been the first (and last) captain of the ship, and, to return to the BDO qua BDO, the engines are reparable and the dome retractable; we get a good Nightfall scene with surprisingly little panic.

Janus

BDO of the Day: Janus

Today’s Big Dumb Object (BDO) is Janus, the moon of Saturn, which in Alastair Reynolds' Pushing Ice turns out to be much more than it seems. It turns out that Janus’s weird co-orbit with Epimetheus wasn’t an accident but an alien plot to disguise a BDO as a moon until humanity became interesting enough to chase a suddenly de-iced and de-orbiting Janus out of the solar system as it makes its surprise trip to Virgo. The anti-heroes of the story don’t actually intend to pursue Janus that far; they were out mining ice from a comet when Janus took flight, and they happened to be the only ship close enough to its flight path to investigate.

Spoilers

Due to forces beyond their immediate understanding, the humans end up stuck on Janus for the long haul. They build a small colony on some of the remaining ice cover of Janus, and draw power from the mysterious machinery that seems to form the vast majority of the erstwhile moon. No numbers are given for the thickness of ice lost, but the general impression one gets from the story is that Janus is about as big as it ever was, which is to say, about 200 kilometers (125 miles) in its longest dimension, and 716,000 cubic kilometers, or 172,000 cubic miles, in volume.

The humans barely survive the ordeal, and never gain much understanding of the mechanical workings of Janus or of its language of colorful lights. Nor do they find any aliens within; Janus seems to be fully automated and nothing more than a trap intended to transport them to Virgo. They know from observations made back in their own solar system that another megastructure awaits them there. A pipe-shaped skeletal structure “seventeen or eighteen light-seconds wide, and nearly 3 light minutes long” hovers at the Lagrange point between the two stars of the binary star system of Alpha Virginis, a.k.a., Spica. (That’s 3 and a quarter million miles in diameter by 33 million miles long.)

However, as they near Spica after twelve years, Janus sprouts a shell and the view of the megastructure is hidden from them for another year or so. Eventually, however, aliens cut a hole through the shell, and the humans see the empty megastructural tube they’ve been expecting. There are doors at the ends of the tube, but they’re closed.

They make first contact with the alien drillers, who are cagey about their technology and knowledge, but do provide resurrection and rejuvenation services freely. This allows the story’s timeline to drag on for several more decades than one might have expected or wanted. On the bright side, a resurrection leads to social change in the odd culture that has developed on Janus; the rather psychopathic character who was in charge for most of the story to date is replaced by the anointed heroine of the story, Bella Lind.

(Bella was anointed in a rather disappointing frame story in which far future humans discuss her vital importance to all humanity, so I spent the whole story waiting for her amazing contribution to mankind to happen. It turns out to be some silly CNN interviews she did on the way to investigate Janus that somehow inspired…something, I’m not sure what. In return for this great gift, the future humans send out a package of magical nanotechnology to help her, and she wastes it all undoing a mess made by the psychopath in one neighborhood on Janus, even though the psychopath has already managed to doom all of Janus by that point in the story by betraying humanity to some hostile aliens. The magical nanotech also tells Bella that they’re not at Spica anymore, that Janus only picked up more relativistic speed there and sped away far, far into the future, which is how someone from Bella’s far future could contact a famous character of the past like Bella.)

The psychopath redeems herself—not through any convincing repentance of her destructive behavior, but by going out the hole Janus has blown in the tube and sending back pictures of this third megastructure. And boy, is it mega. The tube the humans used to inhabit before the perverse destruction of Janus, is just one glowing twig in a braided rope that itself is only a small part of a “torus of light” the size of an entire solar system. Things are not going well here at the end of time, however; the center of the torus is missing like the megastructure’s creators, and the ropes leading to it are as frayed as the relations between the various alien species within the structure.

There are some impressive BDOs in this story, but the apparent failure of the megastructure builders to survive their project of creating a congress or zoo at the end of the universe, and the many actual failures of the humans to behave decently, never mind heroically, make this story more depressing than your average abandoned BDO story. The flip side of the sense of wonder is a sense of horror.

Globus Cassus

BDO of the Day: Globus Cassus

Today’s Big Dumb Object (BDO) is the Globus Cassus, a sort of incomplete Dyson Sphere made by sucking the magma out of the center of the Earth to build a much larger, inverted and punctuated structure around it. Unlike your typical science fiction BDO, it’s the invention of Swiss architect and artist Christian Waldvogel (who thus neglected to use the appropriate magical materials to hold the megastructure together).

unattributed art from the defunct website globus-cassus.org (CC BY-SA 3.0)

unattributed art from the defunct website globus-cassus.org (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Although the creator wrote a book, put some information about it on his own site and created an “open source” wiki devoted to it, nowadays the site is under construction, the wiki is gone, the book is rare, and the best resources are the Wikipedia entry and an old Damn Interesting article. According to Wikipedia’s numbers, the Globus Cassus would be almost as large as Saturn, with about 200 million square miles of habitable land in addition to oceans, windows, and large uninhabitable regions of low gravity. The moon would remain in place.

The cited diameter (about 50,000 miles) is not enough to produce adequate gravity at the Earth’s current angular velocity. (The structure is built in geosynchronous orbit.) It’s not clear from what remains on the internet whether the intention was to speed up the Globus Cassus at some point during construction, perhaps after the Great Rains—the point at which the Earth is depleted enough that the oceans (and atmosphere) “wander outwards” onto the Globus Cassus.

While not a particularly practical way of transferring the biosphere, the Great Rains are certainly the dramatic high point of the Globus Cassus project.

Megaworldbuilding

Megaworldbuilding

The NaNoWriMo forums have opened, and I posted some questions to myself qua megaworldbuilder. Since the forums are deleted every year, I’ve preserved them for posterity here:

Is the megastructure full of people, only sparsely populated, or entirely empty?

Do my characters know they’re not on a normal planet? Are they natives and/or do the natives know? Are they descended from the builders or are they more recent colonists?

Why was the megastructure built? Is it abandoned like it (typically) looks, or it is a trap of some sort?

How do my characters get around on something so big it would take years to get from point A to point B by any natural means? Is there a high-speed transit system built in? Is the economy (especially food production) fully automated, mechanized like ours, or entirely reliant on manual labor?

Is the structure completely uniform, or is there some interesting spot they’re trying to reach or might end up at accidentally?

Is the environment completely uniform and Earth-like, or are there alien and/or uninhabitable regions? What separates such regions from each other?

Is there an exact copy of Earth or regions of Earth that might fool my characters into thinking they’re there? (The Ringworld had regions that were copies of know worlds like Earth and Mars.)

There’s always the option of just using the megastructure for a setting, where most of these questions wouldn’t matter to my characters.

I’ve already decided to use my favorite BDO, but if I hadn’t I’d also be asking whether my megastructure was solid or hollow, whether it spun for gravity, was big enough to have gravity, or had none, and whether it was spherical, cylindrical, toroidal, ring-shaped, flat, or something stranger.

Balloon Worlds

BDO of the Day: Balloon Worlds

Today’s Big Dumb Object (BDO) is a balloon world: a sphere of gas not unlike Virga, but without the carbon nanotube shell. Instead, a balloon world is mostly held together by gravity, with a lighter and more fragile skin for protection and pressurization. The usual skin design is asteroid rubble atop a thin, balloon-like membrane, making them quite unlike the hard shells of your typical BDO.

The basic balloon world is asteroid-sized, with an outer skin of some former asteroid’s rubble (asteroids are rarely as solid as they look on TV) protecting the gaseous interior. Smaller structures float around inside the bubble, rotating individually to create gravity. SciFi Ideas has a short article about building balloon asteroid colonies, but the anonymous scientist author maintains an entire blog devoted to the idea. You may recall the friction issues involved in rotating structures within an atmosphere from the megasphere; in this case they’ve been addressed with a novel solution involving flow dividers.

You can super-size your balloon world to sizes we’ve seen before in super-Virgas: Adam Crowl calculates that you can inflate a balloon of Earth-like atmospheric gas to about 21,600 miles in diameter before the self-gravitation that’s holding your balloon together starts working against you and the sphere collapses under its own gravity. If you change your atmosphere to a still-breathable but much lighter heliox mix, you can stretch out to about 285,000 miles in diameter (enclosing 12 quadrillion cubic miles). A balloon world at 250,000 miles in diameter weighs only about one Earth mass between the atmosphere and the shell, yet encloses eight quadrillion cubic miles of space, or two dozen Jupiters by his estimate.

Galaxios

BDO of the Day: Galaxios

Today’s Big Dumb Object (BDO) is the lighter-than-air floating continent within the universe-consuming “topopolis” of the 1998 novel White Light by William Barton and Michael Capobianco. Galaxios is the closest thing in the novel to a well-described structure that makes sense, but that’s only because it’s made of a huge clump of lighter-than-air foliage, and what can one say to that?

I scare-quote “topopolis” because, although the universe-consuming thing is in the tubular shape of a topopolis, it’s actually a parsec in diameter, or 19 trillion miles, and of unknown length. It’s also at least partially filled with much more air than is gravitationally feasible. It may be rotating for gravity or other purposes; the characters trapped within it don’t know the details.

As noted in my topopolis post, the oversexed characters of White Light have not been well received: “it’s as if the cast of a bad porno movie was suddenly transported into what would have otherwise been a fascinating SF novel.” Reading it for myself, I would say that the bigger problem is that the writing and characterization are at the level of bad pornography; the characters' voices are quite difficult to tell apart, and the text is surprisingly lacking in complete English sentences—even setting aside the extreme overuse of ellipses. The story could have had characters that were always thinking about sex for a relevant plot reason, but their own surprise (itself repeated ad nauseam) at their sex-obsession makes it clear that they weren’t intended to be from a hypersexed alternate universe.

The six characters do come from a post-apocalyptic future Earth that, despite the elapsed time since a nuclear war and their possession of significant space industry and colony worlds in other star systems, is only now about to collapse for unspecified reasons. Two of the characters are a male and female space pilot and engineer; the others are her second husband, his housekeeper/whore (details like the legality of her purchase and sexual servitude are, of course, left unspecified), the engineer’s son, and the housekeeper’s daughter.

They end up on a spaceship together for mostly nepotistic reasons, on a mission that is intended merely to protect them from an (of course unexplained) anti-nepotistic roundup. This ship encounters a poorly-described gateway system that propels them to a sequence of poorly-described places; at one of them they meet aliens who tell them about the looming threat of the topopolis.

Eventually they end up in the topopolis itself, discover that this isn’t just a BDO novel but an AU novel—their unexplained faster-than-light drive actually jumps them to adjacent universes (so close in history to their own that no one from the novel’s universe has yet noticed that’s how the drive works)—and the topopolis has a colony of interesting varieties of AU Earthling they can join. These colonists, in turn, want to find the Topopolitans (the creators of the topopolis) in order to experience a poorly-explained but highly hoped-for singularity/heaven.

And then they find it. The characters are just as unsympathetic in heaven as they were on Earth, and heaven has only a tenuous technological basis in the AU-hopping faster than light drive they’ve been using. Sadly, this otherwise interesting twist totally undermines any purpose the topopolis might have been built for, and its purpose for all-consuming all the universes is never revealed. In general, there’s a surfeit of big ideas in this book, but they’re neither explained nor integrated into the plot well enough to make it a good novel.

Solaria

BDO of the Day: Solaria

Today’s Big Dumb Object (BDO) is Solaria, a future series of nested Dyson shells encompassing our entire solar system, described in the Cageworld series by Colin Kapp. Solaria is a fairly well-executed BDO, with magic (mainly the Exis field) credited in all the right places. The series falls into much more mundane traps than any miscalculation or misunderstandings about the force of gravity.

Cageworld 1

In the first volume, Our Heroes leave their home shell, the Mars shell, on a mysterious Search for the Sun (1982/1983) as well as for Zeus, the artificial intelligence charged with creating and maintaining Solaria. The Mars shell is as vast as a Dyson shell should be, and a suitable number of people live on the outside of it, where the gravity is. (It seems thick enough to produce its own gravity.) Legend and dim memory report inner shells: an Earth shell at Earth’s orbit, a Venus shell, and even a Mercury shell.

Solaria has two additional features: the emigration spokes through which shuttles travel, carrying any excess population ever outward to unknown shells from which they can never return, and the cageworlds: entire planets trapped in vacuum bubbles within the shell material. Each shell has a generous helping of cageworlds evenly scattered about its equator, and there is speculation (never verified) that they predate the shells and were used in the building process somehow.

In order to pursue their journey inward, Our Heroes take an experimental ship through the small opening at the top of a Mars cageworld bubble. They land on the cageworld, have pulp-style adventures with their ever-varying isolated inhabitants, and continue out the other end of the bubble. This first shell-world is about 8,000 miles in diameter; the shells themselves tend to average in the neighborhood of 10,000 miles in diameter. Our Heroes quickly discover that Zeus is in no way excited to meet them, but they soldier on.

The surface area of Earth shell is reported to be a hundred quadrillion (1017) square miles, and Our Heroes approximate its population density as the same as that of Mars: 10,000 per square mile with only half of the surface habitable, or 500 quintillion (5020) people. It’s a steampunk shell on which Our Heroes have a brief adventure, and then continue on to the next cageworld, designated E12. Of course the cageworld turns out, purely accidentally, to be Earth herself, sadly neglected by Zeus. Still, Our Heroes pass through to the Venus shell, where they believe Zeus resides.

One important side-adventure is the discovery of a lab planet on which Zeus is trying to evolve new species, including, Our Heroes fear, new, more packable, species of Man. Eventually they find and talk to Zeus. In the process of negotiating with Him, Our Heroes get to proceed farther to the Mercury shell and see the Sun from one of its cageworlds. Negotiations with Zeus end well enough, considering that he comes off as quite insane in this series, and the mission rolls back to Mars.

Cageworld 2

In The Lost Worlds of Cronos (1982/1983) Niklas Boxa, a student at the new-founded Centre for Solarian Studies on Mars shell, postulates an unknown shell between the Jupiter and Saturn shells. This shell is eventually found and explored by Boxa (for whom it is named) via emigration spoke, and by Our Heroes by ship. They have more fantastical adventures of the pulpy sort. Zeus, of course, interferes, because whatever détente they have means little beside his inexplicable whims.

The contribution of the novel to the series is mainly the discovery of the overpopulated Boxa shell, a layer-cake arrangement stuffed full of marsupialized, easily stacked human-like beings with night vision—more, Our Heroes estimate, than all of normal humanity on all the other shells. They fear Zeus intends to supplant humanity with marsupialanity in order to carry out the letter, if not the spirit, of its charge to support the ceaseless increase of Man.

Cageworld 3

The Tyrant of Hades (1982/1984) is a mystery on the vastly underpopulated Uranus shell. Zeus, having lost control over that distant region, allows Our Heroes to explore all the way out to that shell in their usual, pulpy way. Notable discoveries of this novel include the fact that Zeus must operate through semi-independent agents at distances where communication is delayed by hours. (There is no ansible here.)

Cageworld 4

Star Search (1983/1984) leads, inevitably, to the stars, by way of Neptune and Pluto shells, with the usual pulpy adventures along the way. Interestingly, Pluto shell shows the limits of the magic technology with which these shells are held together; bits of the Exis field poke up onto the shell surface, making travel challenging. Nevertheless, humanity is establishing itself there.

And yet, the expected sky and stars are not found over the Pluto shell, though clearly another habitable shell cannot be surrounding it. With more travel Our Heroes discover the barrier, a pure Exis shell meant to protect humanity from construction projects on the outside. Zeus objects, but local agents let Our Heroes through it to see the stars, and something else.

Here the series ends on a deus ex machina; it turns out crazy Zeus doesn’t seem to know that some of his split personalities/independent agents have been making more shellworlds surrounding new suns outside of Solaria, and positioning them to pick up the excess human population. So there is no Malthusian trap after all, and Zeus has been making marsupials to no end.

Review

I read this series for the Big Dumb Object, and found myself far more entertained than I expected. The Cageworlds stuck into gaps within the Dyson shells are a great idea in their own right, and they also provide a new lost colony of humanity or weird project of Zeus’s with every shell crossing in the series. Along with some free-floating objects in intershellar space, they add up to a constant stream of new ideas and adventures.

This series was a fun read, if you can suspend your disbelief long enough for some short pulpy adventures in the fine old Barsoomian tradition. The cageworlds, shells, and other fragments of BDO are reasonably believable and entertaining, Zeus a bit less so. I haven’t gone into details about the characters because though their stories and skills are interesting, they get through the series without being deep or changing in any way.

The premise of the series is big and dumb: not even ten nested Dyson spheres can solve the Malthusian trap for long, and the crazed computer deals with the problem in the stupidest ways it can think of. In reality, people do not reproduce in a Malthusian way; crowding and prosperity cut birth rates, never mind disease and war happening well before you’ve packed a hundred thousand people into a square mile (on the overpopulated Jupiter shell).

Even if you accept the premise that people will reproduce exponentially if left to their own devices, the way to squelch that is not to force randomly selected humans to emigrate, but to force third children to emigrate. Humanity in Solaris lives in horror of emigration, so why not direct it in a way that keeps that third child from ever being born?

Update

Minor edits to incorporate my brief Goodreads review.

Alderson Disk

BDO of the Day: Alderson Disk

Today’s Big Dumb Object (BDO) is an Alderson Disk, a finite plane with a sun in a hole at its center. The invention of Dan Alderson, it was popularized in Larry Niven’s classic megastructures essay, where he also mentions bobbing the sun up and down to replace the perpetual twilight with actual night and day, and the necessity of a wall to retain the atmosphere at the inner edge.

I blogged about another Alderson disk previously, in Missile Gap by Charlie Stross.

A Brief History of BDOs

A Brief History of BDOs

Via reddit: Today’s Big Dumb Object (BDO) story is a non-fiction recap of the genre, “A Brief History of the Big Dumb Object Story in Science Fiction” by James Davis Nicoll at Tor. He thinks “the heyday of the BDO seems to be over,” because of the zeitgeist or the stock plots—I would say it’s the difficulty of fitting a human-sized story to an inhuman-sized setting—and he laments the lack of women writing BDO stories, though the commenters come up with plenty of recent examples, one of them even female.

Spinneret

BDO of the Day: Spinneret

Today’s Big Dumb Object (BDO) is not the Spinneret, an alien artifact accidentally discovered on a metal-poor world by humanity’s first colonists (aliens, humanity has recently discovered, have taken all the good worlds already) in Timothy Zahn’s eponymous 1985 novel, but (spoilers!) another object it eventually leads them to.

The Spinneret itself is responsible for having sucked every trace of metal out of the ground of the colony world. The colonists discover it, still working, after it sucks all their iron tools, metal shelving, and vital fertilizer ingredients away, suspiciously spitting a filament of strong, sticky unobtanium out of a nearby volcano into space soon afterwards. You’d think that would lead the scientists immediately down the cone of the not-really-a-volcano to the machinery below, but no. The volcano remains a dead-end until it’s needed much later in the plot; instead the humans find the machinery behind the Spinneret by a more clever and circuitous route.

The machine has much more than just a control room; an entire underground alien colony apparently once surrounded the Spinneret despite its evident ability to spin unsupervised in 2016 (novel-time). But no Spinners remain, only their machinery and guard robots, which are somehow still operational after a hundred thousand years.

Review

I’ll interrupt the plot summary for a brief review. When the Spinneret complex was discovered, I began to worry that it was the rumored BDO of the novel, and no bigger, dumber object would ever come to light. I put the book down several times because I was in it for a bigger BDO and that BDO was not materializing, while even the smaller, smarter object was a slog to read about.

Other reviews are particularly harsh on the weak characters and plot holes, but I found the book such hard going because of all the human-human politics, slightly alleviated by a side order of human-alien politics. The political conflict is not based on any explicit philosophical differences between the characters or countries, but rather some basic assumption on the part of the author that people and countries will go on bickering even with ten or twenty alien species breathing down their necks. That may be true, but a whole novel about it is not science fiction; it’s political fiction.

Fortunately, my suffering was eventually rewarded with an actual BDO, revealed in the penultimate chapter a la Across a Billion Years. But be warned, this was not a BDO novel—the back describes it as a techonological thriller—and the BDO is even more of a tragic MacGuffin than Robert Silverberg’s.

BDO

In the course of a rebellion motivated (for all I could tell) purely by bickering, the main characters finally take the volcanic route into the partially-explored Spinneret complex. They find a Spinner starship still sitting on its underground pad, ready to launch out the cone. Soon afterward, the political situation forces their leader’s hand into an apparent voyage of exploration aboard that ship (though his motives turn out to be political after all), and in this way they discover a new kind of star drive and the Spinners' Dyson sphere.

image by Adam Burn

image by Adam Burn

There are quite a few interesting things about this Dyson sphere: it’s incomplete, it’s damaged to boot, it’s not a habitable sphere (on either side) but merely a disguise intended to make the yellow sun inside look like a red giant from a distance, and it’s heated (by some unspecified means involving asteroid-shaped masses chained to the outside) to red giant temperature.

The function of the Spinneret was to make the unobtanium sphere-building material that intentionally mimics the spectrum of a red giant. Because the Spinners, despite their unobtainum and Dyson-shell heating powers, were homebodies who couldn’t conceive of another way to fight their mysterious enemies than hiding from them. Nevertheless, their planet was depopulated in the attack that also shot holes though the sphere—though it’s not clear why the other aliens shot it up, since they could have just flown straight in the bigger hole where the sphere was unfinished. Aliens. So…alien.

So there’s a BDO at the end, but it’s not described very well; the approach to it is largely filtered through one character’s dread about the true fate of the Spinners. The ship is an escape pod that mostly steers itself; the humans don’t have much of a handle on the instruments and are reduced to looking out the window with a telescope—and closer to the sun, a pinhole. This puts no numbers on the bigness of the BDO or the hole in it.

I had to reread the chapter to figure out whether the Spinners' home planet was inside or outside the shell; it was never stated explicitly, only implied that it was inside. There was no landing on the planet to observe the red sky, nor any detailed description of the edge of the incomplete sphere, never mind the trip inside. But there’s another chapter and a half of politics afterwards, just to kill any sense of wonder you may have pulled together on your own out of the sketchy description.

Bishop Ring

BDO of the Day: Bishop Ring

Today’s Big Dumb Object (BDO) is a Bishop Ring, the little cousin of a Ringworld, and the bigger brother of the Stanford torus, a rotating ring-shaped enclosed habitat about a mile in major diameter and 450 feet in minor (tube) diameter:

As the O'Neill cylinder was supersized into the McKendree cylinder by the discovery of carbon nanotubes, the Stanford torus was supersized into the Bishop ring. In this case, it’s also large enough not to need enclosure, only walls to hold in the atmosphere. The Bishop ring as proposed by Forrest Bishop is 1240 miles in major diameter and 310 miles wide, for a surface area of 1.2 million square miles.

Bishop rings appear, of course, at Orion’s Arm, and in a smaller form in the film Elysium.

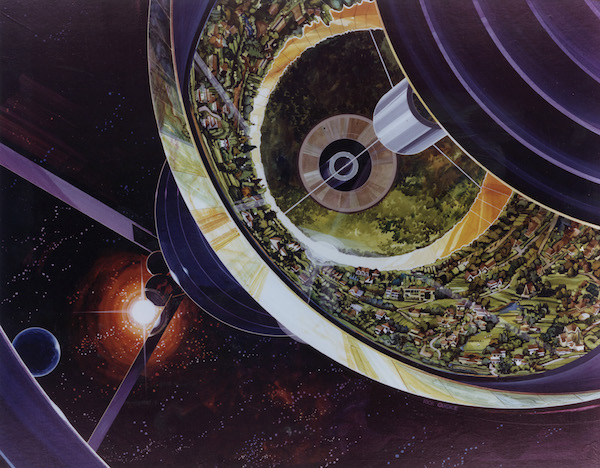

Ringworld

BDO of the Day: Ringworld

Today’s Big Dumb Object (BDO) is a Ringworld, the familiar creation of Larry Niven in his eponymous 1970 novel that later sprouted a series, not to mention inspiring many other big dumb rings of various sizes and kicking off a golden age of BDOs. (Rendezvouz with Rama came out in 1973, and the Orbitsville series began in 1975.)

Niven described the Ringworld again in his classic megastructures essay (Analog, March 1974, emphasis added):

I myself have dreamed up an intermediate step between Dyson spheres andplanets. Build a ring 93 million miles in radius—one Earth orbit—which would make it 600 million miles long. If we have the mass of Jupiter to work with, and if we make it a million miles wide, we get a thickness of about a thousand meters. The Ringworld would thus be much sturdier than a Dyson sphere.

There are other advantages. We can spin it for gravity. A rotation on its axis of 770 miles/second would give the Ringworld one gravity outward. We wouldn’t even have to roof it over. Put walls a thousand miles high at each rim, aimed inward at the sun, and very little of the air will leak over the edges.

Set up an inner ring of shadow squares-light orbiting structures to block out part of the sunlight-and we can have day-and-night cycles in whatever period we like. And we can see the stars, unlike the inhabitants of a Dyson sphere.

The thing is roomy enough; three million times the area of the Earth. It will be some time before anyone complains of the crowding. As with most of these structures, our landscape is optional, a challenge to engineer and artist alike. A look at the outer surface of a Ringworld or Dyson sphere would be most instructive. Seas would show as bulges, mountains as dents. River beds and river deltas would be sculpted in; there would be no room for erosion on something as thin as a Ringworld or a Dyson sphere.

Il Mondo ad Anello de “I burattinai” di Larry Niven by Hill

Il Mondo ad Anello de “I burattinai” di Larry Niven by Hill

Niven goes on to say that the seas would be shallow qua purely cosmetic, but that doesn’t seem like the proper way to make an environment to me. He also explains how to move a Ringworld by moving its sun with “a jet of [solar] gas along the Ringworld axis of rotation”. But some things went unexplained until the sequel, The Ringworld Engineers (1980), like how the ringworld stays in its unstable orbit.

For more details and pictures, see Isaac Arthur’s video about ringworlds.

Banks Orbital

BDO of the Day: Banks Orbital

Today’s Big Dumb Object (BDO) is a Banks Orbital, Orbital Ring, or simply Orbital, the little brother of Larry Niven’s more famous Ringworld. Introduced in 1987 by Iain M. Banks in Consider Phlebas, Orbitals solve the ringworld’s daylight and orbital stability problems by being the perfect size.

An Orbital orbits its sun in the usual fashion, not as a giant unstable ring with its center of gravity at the sun. By setting the Orbital at an angle and rotating it at the speed desired to maintain gravity, it can have a normal day-night cycle as well as seasons, although it will not have regional variations in insolation like our arctic or tropics. Like a ringworld’s, the Orbitals' atmosphere is held in by rimwalls, though of only half the height (300 miles) and transparent rather than disguised as mountains.

There is only one diameter of Orbital for any pair of gravity and day length requirements; for an Earth gravity and an Earth day, it’s a diameter of about 2.3 million miles. The width can vary; at a width of 3,000 miles, an Earth-like Orbital would have 22 billion square miles or so of surface, or about a hundred Earths' worth. (Culture Orbitals are a bit smaller due to their shorter day.) Though only a drop in the three-million-Earth bucket of a Ringworld, it still requires exotic materials to build.

Model of a Banks Orbital by Giuseppe Gerbino

Model of a Banks Orbital by Giuseppe Gerbino

Though Orbitals are big, they’re not dumb in the ancient abandoned BDO sense; they are an ongoing project of a living civilization. For more about the Culture and how they build their Orbitals, see Banks' essay “A Few Notes on The Culture.”

Halo

BDO of the Day: Halo

Today’s Big Dumb Object (BDO) is a Halo Ring or simply Halo, from the video game of the same name. At a diameter of about 6,000 miles, a Halo is closer in size to a Bishop Ring than to a Banks Orbital, though it’s closest of all to the diameter of the Earth.

Halos (there are many) are about 200 miles wide, yielding a surface area of 4 million square miles, which is only a fiftieth of an Earth (or a long, skinny Canada). But what they lack in size, they make up for in dumbness. Unlike Banks' populous, expanding Orbital collection, the Halos are abandoned ancient technology with an apocalyptic purpose. For more on Halos, see the official Halo site, Gamasutra’s Halo Science 101, or Halopedia (including their list of Halo novels).

Hoopworld

BDO of the Day: Hoopworld

Today’s Big Dumb Object (BDO) is a Hoopworld or toroidal planet shaped like a doughnut. While it’s possible that such planets might form natually, they would be unstable over the long term. Anders Sandberg evaluates a couple of possible toroidal planets of “natural” size (whether natural or artificially constructed)—that is, up to about six times the surface area of the Earth.

One disadvantage of the natural size is that the day length on a toroidal planet is only a few hours. Orion’s Arm postulates a less natural hoopworld with a more natural day length: about 90,000 miles across, and about an Earth-sized diameter in cross-section.

To make larger hoopworlds like that, you need some artificial BDO construction and maintenance methods. In Episode 7 of Isaac Arthur’s Megastructures video series, he discusses exotic construction methods for hoopworlds and suggests linking your hoopworlds together into a chain around a sun (just because you can) or putting a topopolis or more hoopworlds in the middle of it.

BDO Recommendations from Reddit

BDO Recommendations from Reddit

Via reddit again: Today’s Big Dumb Object (BDO) non-story is a thread at Reddit about favorite BDOs. Some of the BDOs aren’t (e.g., Anathem) and others I haven’t read so I can’t vouch for their being actual BDOs (yet): Blame, Marrow!, The Architects of Hyperspace, The Stars Are Legion, The Expanse, Grand Central Arena, Confluence, Vast, Rogue Moon (an oldie), Dark Orbit, ShipStar (Larry Niven and Greg Benford), and Strata (Terry Prachett).

Heaven's River

BDO of the Day: Heaven's River

Today’s Big Dumb Object (BDO) is a spoiler for Bobiverse volume 4, Heaven’s River (2020). In lieu of spoiler space, I will instead start by describing the Bobivese. It’s a series available from Kindle Unlimited about an uploaded human named Bob and his many clones. Volume 1 begins with only one Bob, pre-upload, enjoying a windfall from selling his software company for the big bucks. He spends some of his cash on a cryogenic freezing insurance program and before you can say “Bob’s your uncle”, Bob is waking up dead and uploaded by a dystopian future society.

The author, Dennis E. Taylor, has been criticized for the nature of the future fundamentalist society in which Bob wakes. I am sympathetic to such critiques; I find The Handmaid’s Tale too paranoid to take seriously, but because I picked up the Bobiverse off a list of humorous sci-fi books, I took FAITH as an entertaining parody rather than a paranoiac prediction. Also, FAITH is clearly a part of the general stupid humans tendency towards power politics in the face of looming armageddons, a tendency the Bobs didn’t initially share. By volume 4, the Bob clones are experiencing a lot of “drift”, and the novel is about half intra-Bob politics and half BDO.

The BDO in question is a topopolis with a tube radius of 56 miles, wrapped around its sun three times in the traditional toroidal knot for a length of “literally a billion miles.” The length is broken up into “almost two million” sealable segments 560 miles long; the total area is “more than three hundred billion square miles,” or about 1750 Earths.

The topopolis rotates around its inner axis in the usual way to generate gravity, with the standard non-rotating outer shell to fend off meteor strikes. While there are airlocks and transfer methods to get humanoids from outside the outer shell to inside the topopolis proper, at the time the Bobs approach the topopolis they are mostly unused except by automated maintenance systems. The structure has no windows; instead there is artificial lighting and some vaguely described holographic technology creating the illusion of a normal sky.

The most notable feature of the topopolis is not one, but four river systems flowing the whole way around the knot. The Bobs eventually discover that two of the rivers flow in one direction and the other two in the other direction, though they do mix and mingle inside the segments. There is some passing mention of different weather systems and ecologies in the different segments, but the reader never sees any directly, and the entire habitat appears to be intended to reproduce that of a recently war-torn, dead planet in the same system that is clearly the origin of the otter-like sentient species now inhabiting the BDO.

Topopolises are high-maintenance, so there’s no real notion that the structure has been abandoned. Yet the inhabitants the Bobs meet have been cut off from all significant technology, including the built-in transit system. They are clearly in the process of forgetting they’re on a humanoid-made structure, if not actually devolving to their pre-intelligent state. They make vague references to the Administrator and the Crew, but most inhabitants encounter only the local police forces. Though the Bobs are on an unrelated mission, they do eventually meet both the Crew and the Resistance, and even contact the Administrator.

P.S. I was inspired by today’s BDO to collect all my BDO posts in one convenient spot.

Strata

BDO of the Day: Strata

Today’s Big Dumb Object (BDO) comes from Terry Pratchett’s 1981 science fiction novel Strata. Sadly, the BDO itself involves no stratification; the strata come from the main character’s job of terraforming planets all the way down to the trilobite fossils. Instead, the BDO is a proto-Discworld sans turtles—a sort of miniature Alderson disk enclosed within a snowglobe and lit by fake heavenly bodies.

After reading several “BDO” stories lacking any BDO, I could forgive the lack of true bigness (considering it was flat-Earth-sized rather than a small building one could jog across in under 10 minutes like the little dumb object in Algis Budrys' equally deceptively named Rogue Moon). I very much appreciated the Ringworld-parody aspect of the novel, which lends it a classic BDO feel in which the characters crash on the BDO and dodge the dangers of a primitive society (not to mention each other) while seeking the absent caretakers, or at least their secrets.

There’s an important difference here, though. Instead of being awestruck, our heroine, a planetary engineer herself, is a bit disgusted by the state of disrepair this high-maintenance indulgence has fallen into. She’s also not entirely certain that aliens are behind this BDO (as opposed to rogue elements of galactic society). The clever solution makes up for any erratic bits of the plot up until that point.

Helix

BDO of the Day: Helix

Today’s (more like this year’s) Big Dumb Object (BDO) comes from Eric Brown’s two-book series Helix (2007, reissued in 2023) and Helix Wars (2012).

There’s a tiring amount of framing of the human side of Helix, in which a severely depopulated Earth sends out a lone ship of 4,000 sleeping colonists plus a skeleton crew of six. Eventually, the crew awaken to a crash landing on what they at first think is their target planet. Soon enough, the sun rises over something quite different, a helical planet that the author never quite describes to my satisfaction.

The Helix is a long, skinny megastructure wrapping eight times around a central star to form a single-stranded helix. It seems to be rotating around its cylindrical axis the way a topopolis can, but it also seems to be a solid planet, at least until book 2. The Helix contains approximately ten thousand worlds, divided by ten thousand seas, like a necklace of alternating green(ish) and blue beads.

There are no seasons, though the outer tiers are colder than the central ones. What happens physics-wise at the two ends of the structure is not addressed. The question of whether a solid ring or helix can rotate like a topopolis is moot because Helix Wars reveals that at least some world-beads rotate at different rates, so it must be jointed although no joints are ever shown.

The diameter of this tubular planet isn’t specified until well into book 2, nor is the length of the individual world-beads. The seas are described as a thousand miles wide, i.e., long. Though they seem to serve as buffers between the different atmospheres and geographies of the individual worlds, how this works is also never described. Most of the travel in the books is by spaceship, at an unspecified speed. So in book 1, the biggest clue to the dimension of the world is a statement that “there’s sufficient landmass in the entire helix to contain oven ten thousand planets the size of Earth.” The distance between the tiers (later called circuits) of the Helix is never discussed.

In Helix Wars, a tale of interworld conflict, a few humans get to see the “spine” of the Helix, a tunnel two hundred kilometers (125 miles) in diameter running the length of the Helix, within a wall ten kilometers thick. There’s some unnecessary artificial hollow-earth-style gravity to counteract the shell theorem. The tunnel isn’t really necessary for either the plot or the structure, though gigantic machines within it are somehow supposed to be maintaining everything from a distance of “almost 8,000 kilometers” (4971 miles) from the surface. In addition to this radius, a length for the Helix is also finally provided: 200,000,000 kilometers (124,275,000 miles). These are big numbers, but they’re not big enough; see the calculations below for details.

Both novels provide entertaining adventures involving a reasonable number of worlds and species of the Helix; they’re very much a typical example of the genre rather than one of those novels that provide only a glimpse of the BDO in the last chapter. The lack of physical detail about the Helix in the first novel interfered with my sense of wonder, as did the reliance on magic technology once details were revealed (e.g., the unnecessary artificial gravity in the unnecessary tunnel through the center of the Helix), though my personal BDO construction principles probably don’t matter to the average reader.

Spoilers